This blog is Assignment writing on paper no-105 (History of English literature-from 1350-1900)assigned by Professor Dr. Dilip Barad sir, Head of the English Department of Maharaja Krishnakumarsinhji Bhavnagar University.

Name: Gayatri Nimavat

Paper: 105 (History of English literature-from 1350-1900)

Roll no: 09

Enrollment no: 4069206420220019

Email ID: gayatrinimavat128@gmail.com

Batch: 2022-24 (MA Semester - 1)

Submitted to: S. B. Gardi Department of English,Maharaja Krishnakumarsinhji Bhavnagar University

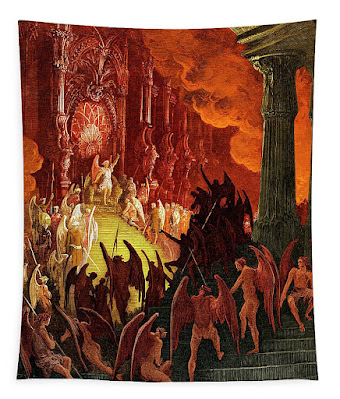

Analysis of John Milton's 'Paradise Lost'

Introduction:

John Milton's Paradise Lost is one of the greatest epic poems in the English language. It tells the story of the Fall of Man, a tale of immense drama and excitement, of rebellion and treachery, of innocence pitted against corruption, in which God and Satan fight a bitter battle for control of mankind's destiny. The struggle rages across three worlds - heaven, hell, and earth - as Satan and his band of rebel angels plot their revenge against God. At the center of the conflict are Adam and Eve, who are motivated by all too human temptations but whose ultimate downfall is unyielding love.

Marked by Milton's characteristic erudition, Paradise Lost is a work epic both in scale and, notoriously, in ambition. For nearly 350 years, it has held generation upon generation of audiences in rapt attention, and its profound influence can be seen in almost every corner of Western culture.

About Author:

John Milton, (born December 9, 1608, London, England, died November 8?, 1674, London?), English poet, pamphleteer, and historian, considered the most significant English author after William Shakespeare. Milton is best known for Paradise Lost, widely regarded as the greatest epic poem in English. Together with Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, it confirms Milton’s reputation as one of the greatest English poets.

John Milton, best known today for his epic poem Paradise Lost, was radically committed to the idea of intellectual liberty. This commitment manifested itself throughout his life, and across his widely varied written works, which included poetry, tracts, speeches, and unpublished, private writings. Politically, it was expressed through Milton’s support of republican, rather than monarchical, forms of government. In his religious writings, too, the concept of free will is always at the forefront. His poetry challenges readers to negotiate moral and aesthetic dilemmas, a learning process designed to enable them, ultimately, to choose more wisely between good and evil.

'Paradise Lost' overview:

Paradise Lost is an epic poem (12 books, totalling more than 10,500 lines) written in blank verse, one of the late works by John Milton, originally issued in 10 books in 1667 and, with Books 7 and 10 each split into two parts, published in 12 books in the second edition of 1674. It is telling the biblical tale of the Fall of Mankind, the moment when Adam and Eve were tempted by Satan to eat the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, and God banished them from the Garden of Eden forever.

John Milton bases his story on the account of the Fall in Genesis, the first book of the Old Testament, promising very early in the poem to ‘justify the ways of God to men’. But he extends and elaborates the story in many other directions too, including narrations of the formation of the universe out of cosmic chaos, the rebellion of Satan and the other fallen angels in Heaven, the creation of the Earth and of mankind, and swathes of fallen, human history.

Many scholars consider Paradise Lost to be one of the greatest poems in the English language. It tells the biblical story of the fall from grace of Adam and Eve (and, by extension, all humanity) in language that is a supreme achievement of rhythm and sound. The 12-book structure, the technique of beginning in medias res (in the middle of the story), the invocation of the muse, and the use of the epic question are all classically inspired. The subject matter, however, is distinctly Christian.

The main characters in the poem are God, Lucifer (Satan), Adam, and Eve. Much has been written about Milton’s powerful and sympathetic characterization of Satan. The Romantic poets William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley saw Satan as the real hero of the poem and applauded his rebellion against the tyranny of Heaven.

Character analysis:

God:

The omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent creator of the universe. He is depicted as pure light by Milton and rules from an unmovable throne at the highest point in Heaven. God is the epitome of reason and intellect, qualities that often make him seem aloof and stern in the poem. His more merciful side is shown through his Son who is of course one of the Trinitarian aspects of God though not the same as God. God creates Man (Adam) and gives him free will, knowing that Man will fall. He also provides his Son, who becomes a man and suffers death, as the means to salvation for Man so that ultimately goodness will completely defeat evil.

Son:

In the doctrine of the Trinity, the Godhead is made up of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. Milton seems to make God the Son not co-eternal with the Father, though the theology here is not absolutely clear. The Son is presented to the angels well after the creation, and God's preference of the Son causes Satan to rebel. The Son creates the Earth (he is referred to as God while doing so). The Son offers himself as a sacrifice to Death as a way to save Man after the Fall. The Son also defeats the rebellious angels and casts them into Hell. He shows the more merciful aspect of God.

Satan:

Before his rebellion, he was known as Lucifer and was second only to God. His envy of the Son creates Sin, and in an incestuous relationship with his daughter, he produces the offspring, Death. His rebellion is easily crushed by the Son, and he is cast into Hell. His goal is to corrupt God's new creations, Man and Earth. He succeeds in bringing about the fall of Adam and Eve but is punished for the act. He can shift his shape and tempts Eve in the form of a serpent. He appears noble to Man but not in comparison to God.

Adam:

The first human, created by God from the dust of Earth. He is part of God's creation after the rebellious angels have been defeated. At first Adam (and Eve) can talk with angels and seem destined to become like angels if they follow God's commands. Adam eats the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge because he cannot bear losing Eve. His inordinate desire for Eve is his downfall. He and Eve feud after the fall but are reconciled. They eventually go forth together to face the world and death.

Eve:

Eve is the first woman, created by God from Adam's rib as a companion for him. She is more physically attractive than Adam, but not as strong physically or intellectually. She is seduced and tricked by Satan in the form of the serpent and eats the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. She then tempts Adam whose love and desire for her is so strong that he eats the fruit rather than risk separation from Eve. Ultimately, Eve brings about reconciliation with Adam when she begs forgiveness from him. God promises that her seed will eventually bruise the head of the serpent, symbolically referring to Jesus overcoming Death and Satan.

Major Themes:

1 Disobedience:

The first part of Milton's argument hinges on the word disobedience and its opposite, obedience. The universe that Milton imagined with Heaven at the top, Hell at the bottom, and Earth in between is a hierarchical place. God literally sits on a throne at the top of Heaven. Angels are arranged in groups according to their proximity to God. On Earth, Adam is superior to Eve, humans rule over animals. Even in Hell, Satan sits on a throne, higher than the other demons.

The significance of obedience to superiors is not just a matter of Adam and Eve and the Tree of Knowledge; it is a major subject throughout the poem. Satan's rebellion because of jealousy is the first great act of disobedience and commences all that happens in the epic. When Abdiel stands up to Satan in Book V, Abdiel says that God created the angels "in their bright degrees" (838) and adds "His laws our laws" (844). Abdiel's point is that Satan's rebellion because of the Son is wrong because Satan is disobeying a decree of his obvious superior. Satan has no answer to this point except sophistic rigmarole.

2 Eternal Providence:

Milton's theme in Paradise Lost, however, does not end with the idea of disobedience. Milton says that he will also "assert Eternal Providence." If Man had never disobeyed God, death would never have entered the world and Man would have become a kind of lesser angel. Because Adam and Eve gave in to temptation and disobeyed God, they provided the opportunity for God to show love, mercy, and grace so that ultimately the fall produces a greater good than would have happened otherwise.

The general reasoning is that God created Man after the rebellion of Satan. His stated purpose is to show Satan that the rebellious angels will not be missed, that God can create new beings as he sees fit. God gives Man a free will, but at the same time, God being God, knows what Man will do because of free will. Over and over in Paradise Lost, God says that Man has free will, that God knows Man will yield to Satan's temptation, but that he (God) is not the cause of that yielding; He simply knows that it will occur.

3 Justification of God's Ways:

Eternal Providence moves the story to a different level. Death must come into the world, but the Son steps forward with the offer to sacrifice himself to Death in order to defeat Death. Through the Son, God is able to temper divine justice with mercy, grace, and salvation. Without the fall, this divine love would never have been demonstrated. Because Adam and Eve disobeyed God, mercy, grace, and salvation occur through God's love, and all Mankind, by obeying God, can achieve salvation. The fall actually produces a new and higher love from God to Man.

Political contexts:

Paradise Lost incorporates the political tensions of Milton’s own day – he was writing during and after the Civil Wars in England, which saw King Charles I executed and the country temporarily controlled by a republican government, led by Oliver Cromwell, until Charles II returned to take up the throne – but deals complexly with both republicanism and the monarchy. Satan has long been seen by some critics as a republican hero, eloquent and determined, much more charming and persuasive than the ‘tyrannous’ and rather humourless character of God in the poem. But Royalist readers, especially after the Restoration, chose to see Satan as the figure of Cromwell seen through anti-republican eyes: someone who only pretended to believe in equality, who really wanted power for himself and whose project was doomed to fail.

Scientific and philosophical contexts:

In addition to its political resonances, Paradise Lost includes poetic treatments of some of the most important scientific, philosophical and astronomical advances of Milton’s time. The poem offers insights into the animal kingdom, suggests different theories about whether Ptolemy or Copernicus were right about the sun revolving around the earth or vice versa and asks big, potentially controversial questions about the nature of God and religious worship.

'Paradise Lost' and Mary Shelley’s 'Frankenstein':

'Paradise Lost' was a source of inspiration and fascination for Romantic poets such as William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley. The Romantic interpretation of Satan as the hero of Paradise Lost stems from Blake’s statement that Milton was ‘of the Devil’s party without knowing it’. Shelley wrote in A Defence of Poetry that ‘nothing can exceed the energy and magnificence of the character of Satan as expressed in Paradise Lost’.

The poem was also a crucial influence on Frankenstein. Shelley gave his wife Mary Shelley a copy of Paradise Lost on 6 June 1815. Milton is thought to have visited Villa Diodati, a place on the banks of Lake Geneva where Mary Shelley first conceived the idea for Frankenstein.

In the novel, Mary Shelley highlights the connections between her work and Milton’s poem. The creature also reads the poem with ‘wonder and awe’ as part of his self-education.

The circumstances of the creature and Frankenstein echo many aspects of Milton’s poem: being expelled or refused access to Paradise, having or not having a partner, having or not having the chance of redemption, playing God by creating man.

Frankenstein recognises that ‘like the archangel who aspired to omnipotence, I am chained in an eternal hell’. The creature also compares himself to Satan. Expelled from human society, the creature falls from light into darkness. As he says at the end of the novel, ‘the fallen angel becomes a malignant devil’. His resolution to commit acts of aggression against people around him echoes Satan’s ‘Evil, be thou my Good’.

Conclusion:

In the end, Milton chose not to copy Homer and Virgil, but to create a Christian epic. His creation is still a work of great magnitude in an elevated style. Milton chose not to write in hexameters or in rhyme because of the natural limitations of English. Instead he wrote in unrhymed iambic pentameter, or blank verse, the most natural of poetic techniques in English. He also chose a new kind of heroism to magnify and ultimately created a new sort of epic, a Christian epic that focuses not on the military actions that create a nation but on the moral actions that create a world.

References:

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Paradise Lost". Encyclopedia Britannica, 9 Mar. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Paradise-Lost-epic-poem-by-Milton Accessed 5 November 2022.

Labriola, Albert C.. "John Milton". Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Aug. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Milton. Accessed 5 November 2022.

Lehnhof, Kent R. “‘Paradise Lost’ and the Concept of Creation.” South Central Review, vol. 21, no. 2, 2004, pp. 15–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40039808. Accessed 5 Nov. 2022.

McColley, Grant. “Paradise Lost.” The Harvard Theological Review, vol. 32, no. 3, 1939, pp. 181–235. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1508278. Accessed 5 Nov. 2022.

Steadman, John M. “The Idea of Satan as the Hero of ‘Paradise Lost.’” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 120, no. 4, 1976, pp. 253–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/986321. Accessed 5 Nov. 2022.

Word count: 2439

Images : 17

No comments:

Post a Comment